Satış proqramı, anbar proqramı - Tanks_of_South_Korea

TACİR.PRO müəssisə və təşkilatların anbarlarında, topdan və pərakəndə satış məntəqələrində mal-material, pul vəsaitləri qeydiyyatının avtomatlaşdırılması, borclara operativ nəzarət edilməsi, geniş hesabatların əldə edilməsi məqsədilə tərtib edilmişdir.

Proqram təminatının tam video təlimləri ilə bu keçiddən (İstifadə qaydası) tanış ola bilərsiniz. Proqram təminatını bu keçiddən (Yüklə) yükləyə bilərsiz.

Tacir.PRO haqqında ətraflı məlumat üçün keçid

Wikipediadan təsadüfi məlumatlar : Hayao Miyazaki

Hayao Miyazaki | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

宮崎 駿 | |||||

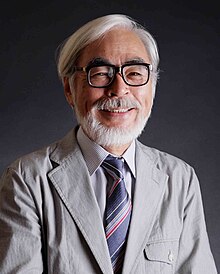

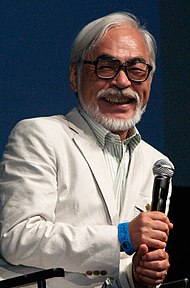

Miyazaki in 2012 | |||||

| Born | January 5, 1941 Tokyo City, Tokyo Prefecture, Empire of Japan | ||||

| Other names |

| ||||

| Alma mater | Gakushuin University | ||||

| Occupations |

| ||||

| Years active | 1963–present | ||||

| Employers |

| ||||

| Spouse |

Akemi Ōta (m. 1965) | ||||

| Children | 2, including Goro | ||||

| Relatives | Daisuke Tsutsumi (nephew-in-law) | ||||

| Japanese name | |||||

| Kanji | 宮崎 駿 | ||||

| |||||

| Signature | |||||

| |||||

Hayao Miyazaki (宮崎 駿 or 宮﨑 駿, Miyazaki Hayao, Japanese: [mijaꜜzaki hajao]; born January 5, 1941) is a Japanese animator, filmmaker, and manga artist. A founder of Studio Ghibli, he has attained international acclaim as a masterful storyteller and creator of Japanese animated feature films, and is widely regarded as one of the most accomplished filmmakers in the history of animation.

Born in Tokyo City in the Empire of Japan, Miyazaki expressed interest in manga and animation from an early age. He joined Toei Animation in 1963, working as an inbetween artist and key animator on films like Gulliver's Travels Beyond the Moon (1965), Puss in Boots (1969), and Animal Treasure Island (1971), before moving to A-Pro in 1971, where he co-directed Lupin the Third Part I (1971–1972) alongside Isao Takahata. After moving to Zuiyō Eizō (later Nippon Animation) in 1973, Miyazaki worked as an animator on World Masterpiece Theater and directed the television series Future Boy Conan (1978). He joined Tokyo Movie Shinsha in 1979 to direct his first feature film The Castle of Cagliostro (1979) and the television series Sherlock Hound (1984–1985). He wrote and illustrated the manga Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1982–1994) and directed the 1984 film adaptation produced by Topcraft.

Miyazaki co-founded Studio Ghibli in 1985, writing and directing films such as Laputa: Castle in the Sky (1986), My Neighbor Totoro (1988), Kiki's Delivery Service (1989), and Porco Rosso (1992), which were met with critical and commercial success in Japan. Miyazaki's Princess Mononoke (1997) was the first animated film to win the Japan Academy Film Prize for Picture of the Year and briefly became the highest-grossing film in Japan; its Western distribution increased Ghibli's worldwide popularity and influence. Spirited Away (2001) became Japan's highest-grossing film and won the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature; it is frequently ranked among the greatest films of the 21st century. Miyazaki's later films—Howl's Moving Castle (2004), Ponyo (2008), and The Wind Rises (2013)—also enjoyed critical and commercial success. He retired from feature films in 2013 but later returned to make The Boy and the Heron (2023), which won the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature.

Miyazaki's works are frequently subject to scholarly analysis and have been characterized by the recurrence of themes such as humanity's relationship with nature and technology, the importance of art and craftsmanship, and the difficulty of maintaining a pacifist ethic in a violent world. His protagonists are often strong girls or young women, and several of his films present morally ambiguous antagonists with redeeming qualities. Miyazaki's works have been highly praised and awarded; he was named a Person of Cultural Merit for outstanding cultural contributions in 2012, and received the Academy Honorary Award for his impact on animation and cinema in 2014. Miyazaki has frequently been cited as an inspiration for numerous animators, directors, and writers.

Early life

[edit]Hayao Miyazaki was born on January 5, 1941, in the town Akebono-cho in Hongō, Tokyo City, Empire of Japan, the second of four sons.[1][2][3][a] His father, Katsuji Miyazaki (born 1915),[1] was the director of Miyazaki Airplane, his brother's company,[5] which manufactured rudders for fighter planes during World War II.[4] The business allowed his family to remain affluent during Miyazaki's early life.[6][b] Miyazaki's father enjoyed purchasing paintings and demonstrating them to guests, but otherwise had little known artistic understanding.[3] He was in the Imperial Japanese Army around 1940, discharged and lectured about disloyalty after declaring to his commanding officer that he wished not to fight because of his wife and young child.[8] According to Miyazaki, his father often told him about his exploits, claiming he continued to attend nightclubs after turning 70.[9] Katsuji Miyazaki died on March 18, 1993.[10] After his death, Miyazaki felt he had often looked at his father negatively and that he had never said anything "lofty or inspiring".[9] He regretted not having a serious discussion with his father, and felt he had inherited his "anarchistic feelings and his lack of concern about embracing contradictions".[9]

Some of Miyazaki's earliest memories are of "bombed-out cities".[13] In 1944, when he was three years old, Miyazaki's family evacuated to Utsunomiya.[4] After the bombing of Utsunomiya in July 1945, he and his family evacuated to Kanuma.[6] The bombing left a lasting impression on Miyazaki, then aged four.[6] As a child, Miyazaki suffered from digestive problems, and was told he would not live beyond 20, making him feel like an outcast;[11][14] he considered himself "clumsy and weak", protected at school by his older brother.[15] From 1947 to 1955, Miyazaki's mother Yoshiko suffered from spinal tuberculosis; she spent the first few years in hospital before being nursed from home,[4] forcing Miyazaki and his siblings to take over domestic duties.[16] Yoshiko was frugal,[3] and described as a strict, intellectual woman who regularly questioned "socially accepted norms".[5] She was closest with Miyazaki, and had a strong influence on him and his later work.[3][c] Yoshiko Miyazaki died in July 1983 at the age of 72.[20][21]

Miyazaki began school as an evacuee in 1947,[4] at an elementary school in Utsunomiya, completing the first through third grades.[22] After his family moved back to Suginami-ku in 1950,[22][15] Miyazaki completed the fourth grade at Ōmiya Elementary School, and fifth grade at Eifuku Elementary School, which was newly established after splitting off from Ōmiya Elementary. After graduating from Eifuku as part of the first graduating class,[22] he attended Ōmiya Junior High School.[23] He aspired to become a manga artist,[24] but discovered he could not draw people; instead, he drew planes, tanks, and battleships for several years.[24] Miyazaki was influenced by several manga artists, such as Tetsuji Fukushima, Soji Yamakawa and Osamu Tezuka. Miyazaki destroyed much of his early work, believing it was "bad form" to copy Tezuka's style as it was hindering his own development as an artist.[25][26][27] He preferred to see artists like Tezuka as fellow artists rather than idols to worship.[26] Around this time, Miyazaki often saw movies with his father, who was an avid moviegoer; memorable films for Miyazaki include Meshi (1951) and Tasogare Sakaba (1955).[28]

After graduating from Ōmiya Junior High, Miyazaki attended Toyotama High School.[28] During his third and final year, Miyazaki's interest in animation was sparked by Panda and the Magic Serpent (1958),[29] Japan's first feature-length animated film in color;[28] he had sneaked out to watch the film instead of studying for his entrance exams.[3] Miyazaki later recounted that, falling in love with its heroine, the film moved him to tears and left a profound impression, prompting him to create work true to his own feelings instead of imitating popular trends;[30][31] he wrote the film's "pure, earnest world" promoted a side of him that "yearned desperately to affirm the world rather than negate it".[31] After graduating from Toyotama, Miyazaki attended Gakushuin University in the department of political economy, majoring in Japanese Industrial Theory;[28] he considered himself a poor student as he instead focused on art.[29] He joined the "Children's Literature Research Club", the "closest thing back then to a comics club";[32] he was sometimes the sole member of the club.[28] In his free time, Miyazaki would visit his art teacher from middle school and sketch in his studio, where the two would drink and "talk about politics, life, all sorts of things".[33] Around this time, he also drew manga; he never completed any stories, but accumulated thousands of pages of the beginnings of stories. He also frequently approached manga publishers to rent their stories. In 1960, Miyazaki was a bystander during the Anpo protests, having developed an interest after seeing photographs in Asahi Graph; by that point, he was too late to participate in the demonstrations.[28] Miyazaki graduated from Gakushuin in 1963 with degrees in political science and economics.[32]

Career

[edit]Early career

[edit]

In 1963, Miyazaki was employed at Toei Doga;[34][32] this was the last year the company hired regularly.[37] He began renting a four-and-a-half tatami (7.4 m2; 80 sq ft) apartment in Nerima, Tokyo, near Toei's studio; the rent was ¥6,000,[37][34] while his salary at Toei was ¥19,500.[37][d] Miyazaki worked as an inbetween artist on the theatrical feature films Doggie March (1963) and Gulliver's Travels Beyond the Moon (1965) and the television anime Wolf Boy Ken (1963).[38] His proposed changes to the ending of Gulliver's Travels Beyond the Moon were accepted by its director; he was uncredited but his work was praised.[39] Miyazaki found inbetween art unsatisfying and wanted to work on more expressive designs.[40] He was a leader in a labor dispute soon after his arrival at Toei, and became chief secretary of its labor union in 1964;[34] its vice-chairman was Isao Takahata, with whom Miyazaki would form a lifelong collaboration and friendship.[40][36] Around this time, Miyazaki questioned his career choice and considered leaving the industry; a screening of The Snow Queen in 1964 moved him, prompting him to continue working "with renewed determination".[41]

During production of the anime series Shōnen Ninja Kaze no Fujimaru (1964–1965), Miyazaki moved from inbetween art to key animation,[42] and worked in the latter role on two episodes of Sally the Witch (1966–1968) and several of Hustle Punch (1965–1966) and Rainbow Sentai Robin (1966–1967).[43][44][45] Concerned that opportunities to work on creative projects and feature films would become scarce following an increase in animated television, Miyazaki volunteered in 1964 to work on the film The Great Adventure of Horus, Prince of the Sun (1968);[46][45] he was chief animator, concept artist, and scene designer,[47] and was credited as "scene designer" to reflect his role.[48] On the film, he worked closely with his mentor, Yasuo Ōtsuka, whose approach to animation profoundly influenced Miyazaki's work.[47] Directed by Takahata, the film was highly praised, and deemed a pivotal work in the evolution of animation,[49][50][51] though its limited release and minimal promotion led to a disappointing box office result,[48] among Toei Animation's worst, which threatened the studio financially.[52] Miyazaki moved to a residence in Higashimurayama after his wedding in October 1965,[53] to Ōizumigakuenchō after the birth of his second son in April 1969,[54] and to Tokorozawa in 1970.[54]

Miyazaki provided key animation for The Wonderful World of Puss 'n Boots (1969), directed by Kimio Yabuki.[55] He created a 12-chapter manga series as a promotional tie-in for the film; the series ran in the Sunday edition of Tokyo Shimbun from January to March 1969.[56][57] Miyazaki later proposed scenes in the screenplay for Flying Phantom Ship (1969) in which military tanks would cause mass hysteria in downtown Tokyo, and was hired to storyboard and animate the scenes.[58] Beginning a shift towards slow-paced productions featuring mostly female protagonists,[59] he provided key animation for Moomin (1969), two episodes of Himitsu no Akko-chan (1969–1970),[60][55] and one episode of Sarutobi Ecchan (1971), and was organizer and key animator for Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves (1971).[61] Under the pseudonym Akitsu Saburō (秋津 三朗), Miyazaki wrote and illustrated the manga People of the Desert, published in 26 installments between September 1969 and March 1970 in Boys and Girls Newspaper (少年少女新聞, Shōnen shōjo shinbun).[54] He was influenced by illustrated stories such as Fukushima's Evil Lord of the Desert (沙漠の魔王, Sabaku no maō).[62] In 1971, Miyazaki developed structure, characters, and designs for Hiroshi Ikeda's adaptation of Animal Treasure Island,[56][57][63] providing key animation and script development.[64] He created the 13-part manga adaptation, printed in Tokyo Shimbun from January to March 1971.[56][57][63]

Miyazaki left Toei Animation in August 1971,[65] having become dissatisfied by the lack of creative prospects and autonomy, and by confrontations with management regarding The Great Adventure of Horus.[66] He followed Takahata and Yōichi Kotabe to A-Pro,[65] where he directed, or co-directed with Takahata, 17 of the 23 episodes of Lupin the Third Part I,[61][67] originally intended as a movie project.[68] This was Miyazaki's directorial debut.[69] He and Takahata were engaged to emphasize the series' humor over its violence.[67] The two also began pre-production on a series based on Astrid Lindgren's Pippi Longstocking books, designing extensive storyboards;[65][70] Miyazaki and Tokyo Movie Shinsha president Yutaka Fujioka traveled to Sweden to secure the rights—Miyazaki's first trip outside Japan and possibly the first overseas trip for any Japanese animator for a production[65][71]—but the series was canceled after they were unable to meet Lindgren, and permission was refused to complete the project.[65][70] Foreign travel left an impression on Miyazaki;[72][73] using concepts, scripts, design, and animation from the project,[68] he wrote, designed and animated two Panda! Go, Panda! shorts in 1972 and 1973, with Takahata as director and Ōtsuka as animation director.[74][75] Their choice of pandas was inspired by the panda craze in Japan at the time.[72]

Miyazaki drew storyboards for the first episode of The Gutsy Frog in 1971 (though they went unused), provided key animation and storyboards for two episodes of Akado Suzunosuke in 1972, and delivered key animation for one episode each of Kōya no Shōnen Isamu (directed by Takahata) and Samurai Giants in 1973.[76] In 1972, he directed a five-minute pilot film for the television series Yuki's Sun; the series was never produced, and the pilot fell into obscurity before resurfacing as part of a Blu-ray release of Miyazaki's works in 2014.[77] In June 1973, Miyazaki and Takahata moved from A-Pro to Zuiyō Eizō,[78][65] where they worked on World Masterpiece Theater, which featured their animation series Heidi, Girl of the Alps, an adaptation of Johanna Spyri's Heidi.[78] The production team wanted the series to set new heights for television animation,[79] and Miyazaki traveled to Switzerland to research and sketch in preparation.[80] Zuiyō Eizō split into two companies in July 1975; Miyazaki and Takahata's branch became Nippon Animation.[78][81] They briefly worked on Dog of Flanders in 1975 before moving on to the larger-scale 3000 Leagues in Search of Mother (1976), directed by Takahata, for which Miyazaki traveled to Argentina and Italy as research.[65][60]

In 1977, Miyazaki was chosen to direct his first animated television series, Future Boy Conan;[82] he directed 24 of the 26 episodes, which were broadcast in 1978.[65][83] Only eight episodes were completed when the series began airing; each episode was completed within ten to fourteen days.[82] An adaptation of Alexander Key's The Incredible Tide,[84] the series features several elements that later reappeared in Miyazaki's work, such as warplanes, airplanes, and environmentalism. Also working on the series was Takahata, Ōtsuka, and Yoshifumi Kondō, whom Miyazaki and Takahata had met at A-Pro.[65][85][86] Visually, Miyazaki was inspired by Paul Grimault's The Adventures of Mr. Wonderbird.[87] Miyazaki did key animation for thirty episodes of the World Masterpiece Theater series Rascal the Raccoon (1977) and provided scene design and organization on the first fifteen episodes of Takahata's Anne of Green Gables before leaving Nippon Animation in 1979.[88][83][89]

Breakthrough films

[edit]Miyazaki moved to Tokyo Movie Shinsha to direct his first feature anime film, The Castle of Cagliostro (1979), an installment of the Lupin III franchise.[90][91] Ōtsuka had approached him to direct the film following the release of Lupin the 3rd: The Mystery of Mamo (1978), and Miyazaki wrote the story with Haruya Yamazaki.[92] Wishing to insert his own creativity into the franchise, Miyazaki inserted several elements and references, inspired by several of Maurice Leblanc's Arsène Lupin novels, on which Lupin III is based,[93] as well as The Adventures of Mr. Wonderbird.[94] Visually, he was inspired by Kagoshima Publishing's Italian Mountain Cities and the Tiber Estuary,[93] reflecting his love for Europe.[94] Production ran for four months[95] and the film was released on December 15, 1979; Miyazaki wished he could have had another month of production.[93] It was well received;[90] Animage readers voted it the best animation of all time—it remained in the top ten for more than fifteen years—and Clarisse the best heroine.[96] In 2005, former princess Sayako Kuroda's wedding dress was reportedly inspired by Clarisse's, having been a fan of Miyazaki and his work.[97] Several Japanese and American filmmakers were inspired by the film, prompting homages in other works.[98]

Miyazaki became a chief animation instructor for new employees at Telecom Animation Film, a subsidiary of Tokyo Movie Shinsha.[99] and subsequently directed two episodes of Lupin the Third Part II under the pseudonym Teruki Tsutomu (照樹 務), which can read as "employee of Telecom".[88] In his role at Telecom, Miyazaki helped train the second wave of employees.[84] Miyazaki provided key animation for one episode of The New Adventures of Gigantor (1980–1981),[100] and directed six episodes of Sherlock Hound in 1981,[101] until legal issues with Arthur Conan Doyle's estate led to a suspension in production;[102][103] Miyazaki was busy with other projects by the time the issues were resolved, and the remaining episodes were directed by Kyôsuke Mikuriya and broadcast from November 1984 to May 1985.[101][103] It was Miyazaki's final television work.[104] In 1982, Miyazaki, Takahata, and Kondō started work on a film adaptation of Little Nemo, but Miyazaki and Takahata left after a few months due to creative clashes with Fujioka (Kondō remained until 1985); the film was completed six years later as Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland (1989).[105][106] Miyazaki spent some time in the United States during the film's production.[107]

After the release of The Castle of Cagliostro, Miyazaki began working on his ideas for an animated film adaptation of Richard Corben's comic book Rowlf and pitched the idea to Yutaka Fujioka at Tokyo Movie Shinsha. In November 1980, a proposal was drawn up to acquire the film rights.[108][109] Around that time, Miyazaki was also approached for a series of magazine articles by Animage's editorial staff. Editors Toshio Suzuki and Osamu Kameyama took some of his ideas to Animage's parent company, Tokuma Shoten, which had been considering funding animated films. Two projects were proposed: Warring States Demon Castle (戦国魔城, Sengoku ma-jō), to be set in the Sengoku period; and the adaptation of Corben's Rowlf. Both were rejected, as the company was unwilling to fund anime not based on existing manga and the rights for Rowlf could not be secured.[110][111] Elements of Miyazaki's proposal for Rowlf were recycled in his later works.[112]

With no films in production, Miyazaki agreed to develop a manga for the magazine, titled Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind;[113][114] he had intended to stop making the manga when he received animation work; while he took some breaks in releases,[115] the manga ultimately ran from February 1982 to March 1994.[116] Miyazaki's busy schedule and perfectionist mindset led to several delays in publications, and on one occasion he withdrew some chapters before publication; he considered its continued publication a burden on his other work.[117] The story, as re-printed in the tankōbon volumes, spans seven volumes for a combined total of 1,060 pages.[116] It sold more than ten million copies in its first two years.[118] Miyazaki drew the episodes primarily in pencil, and it was printed monochrome in sepia-toned ink.[119][120][114] The main character, Nausicaä, was partly inspired by the character from Homer's Odyssey (whom Miyazaki had discovered while reading Bernard Evslin's Dictionary of Grecian Myths) and the Japanese folk tale The Lady who Loved Insects, while the world and ecosystem was based on Miyazaki's readings of scientific, historical, and political writings, such as Sasuke Nakao's Origins of Plant Cultivation and Agriculture, Eiichi Fujimori's The World of Jomon, Paul Carell's Hitler Moves East.[121][122] He was also inspired by the comic series Arzach by Jean Giraud, whom he met while working on the manga.[123][e]

In 1982, Miyazaki assisted with key animation for an unreleased Zorro series, and for the feature film Space Adventure Cobra: The Movie.[101][103] He resigned from Telecom Animation Film in November.[126] Around this time, he wrote the graphic novel The Journey of Shuna, inspired by the Tibetan folk tale "Prince who became a dog". The novel was published by Tokuma Shoten in June 1983,[127] dramatized for radio broadcast in 1987,[128] and published in English as Shuna's Journey in 2022.[129] Hayao Miyazaki's Daydream Data Notes was also irregularly published from November 1984 to October 1994 in Model Graphix;[130] selections of the stories received radio broadcast in 1995.[128] Following the completion of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind's first two volumes, Animage editors suggested a 15-minute short film adaptation. Miyazaki, initially reluctant, countered that an hour-long animation would be more suitable, and Tokuma Shoten agreed on a feature-length film.[105][131][132]

Production began on May 31, 1983, with animation beginning in August;[131] funding was provided through a joint venture between Tokuma Shoten and the advertising agency Hakuhodo, for whom Miyazaki's youngest brother worked. Animation studio Topcraft was chosen as the production house.[105] Miyazaki found some of Topcraft's staff unreliable,[133] and brought on several of his previous collaborators, including Takahata, who served as producer,[134][135] though he was reluctant to do so.[136] Pre-production began on May 31, 1983; Miyazaki encountered difficulties in creating the screenplay, with only sixteen chapters of the manga to work with.[131] Takahata enlisted experimental and minimalist musician Joe Hisaishi to compose the film's score;[136] he subsequently worked on all of Miyazaki's feature films.[137]

For the film, Miyazaki's imagination was sparked by the mercury poisoning of Minamata Bay and how nature responded and thrived in a poisoned environment, using it to create the film's polluted world.[138][139] For the lead role of Nausicaä, Miyazaki cast Sumi Shimamoto, who had impressed him as Clarisse in The Castle of Cagliostro and Maki in Lupin the Third Part II.[140] Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind was created in ten months,[135] and released on March 11, 1984.[141] It grossed ¥1.48 billion at the box office, and made an additional ¥742 million in distribution income.[142] It is often seen as Miyazaki's pivotal work, cementing his reputation as an animator.[143] It was lauded for its positive portrayal of women, particularly Nausicaä.[144][145][146] Several critics have labeled Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind as possessing anti-war and feminist themes; Miyazaki argues otherwise, stating he only wishes to entertain.[147] He felt Nausicaä's ability to understand her opponent rather than simply defeat them meant she had to be female.[148] The successful cooperation on the creation of the manga and the film laid the foundation for other collaborative projects.[149] In April 1984, Miyazaki and Takahata created a studio to handle copyright of their work, naming it Nibariki (meaning "Two-Horse Power", the nickname for the Citroën 2CV, which Miyazaki drove), for which an office was secured in Suginami Ward,[105][150][151] with Miyazaki serving as the senior partner.[117]

Studio Ghibli

[edit]Early films (1985–1995)

[edit]Following the success of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind,[152] Miyazaki and Takahata[f] founded the animation production company Studio Ghibli on June 15, 1985, as a subsidiary of Tokuma Shoten,[155][g] with offices in Kichijōji designed by Miyazaki.[157] Miyazaki named the studio after the Caproni Ca.309[158] and the Italian word meaning "a hot wind that blows in the desert";[159] the name had been registered a year earlier.[160] Suzuki worked for Studio Ghibli as producer,[161] joining full-time in 1989,[162] while Topcraft's Tōru Hara became production manager;[117] Suzuki's role in the creation of the studio and its films has led him to being occasionally named a co-founder,[163][164] and Hara is often viewed as influential to the company's success.[165] Yasuyoshi Tokuma, the founder of Tokuma Shoten, was also closely related to the company's creation, having provided financial backing.[166] Topcraft had been considered as a partner to produce Miyazaki's next film, but the company went bankrupt in 1985.[167] Several staff members subsequently hired at Studio Ghibli—up to 70 full-time and 200 part-time employees in 1985—had previously worked with Miyazaki at different studios, such as Telecom, Topcraft, and Toei Doga, and others like Madhouse, Inc. and Oh! Production.[165]

In 1984, Miyazaki traveled to Wales, drawing the mining villages and communities of Rhondda; he witnessed the miners' strike and admired the miners' dedication to their work and community.[161][168] He was angered by the "military superpowers" of the Roman Empire who conquered the Celts and felt this anguish, alongside the miners' strike, was perceptible in Welsh communities.[169] He returned in May 1985 to research his next film, Laputa: Castle in the Sky, the first by Studio Ghibli.[170][171] Its tight production schedule forced Miyazaki to work all day, including before and after normal working hours, and he wrote lyrics for its end theme.[161] Miyazaki used the floating island of Laputa from Gulliver's Travels in the film.[172] Laputa was released on August 2, 1986, by the Toei Company.[173] It sold around 775,000 tickets,[174] making a modest financial return,[175] though Miyazaki and Suzuki expressed their disappointment with its box office figures of approximately US$2.5 million.[170][176][177]

After the success of Nausicaä, Miyazaki visited Yanagawa and considered imitating it in an animated film, fascinated by its canal system; instead, Takahata directed a live-action documentary about the region, The Story of Yanagawa's Canals (1987). Miyazaki produced and financed the film, and provided several animated sequences.[178][161] Its creation spanned four years, and Miyazaki considered it his social responsibility—to both Japanese society and filmmaking—in seeing it produced.[179] Laputa was created partly to fund production of the documentary, for which Takahata had depleted his funds.[180] In June 1985, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind was released in the United States as Warriors of the Wind, with significant cuts;[161][181] almost 30 minutes of dialogue and character development were removed, erasing parts of its plot and themes.[161][182] Miyazaki and Takahata subsequently refused to consider Western releases of their films for the following decade.[161]

Miyazaki's next film, My Neighbor Totoro, originated in ideas he had as a child; he felt "Totoro is where my consciousness began".[183] An attempt to pitch My Neighbor Totoro to Tokuma Shoten in the early 1980s had been unsuccessful, and Miyazaki faced difficulty in attempting to pitch it again in 1987. Suzuki proposed that Totoro be released as a double bill alongside Takahata's Grave of the Fireflies; as the latter, based on the 1967 short story by Akiyuki Nosaka, had historical value, Suzuki predicted school students would be taken to watch both.[184] Totoro features the theme of the relationship between the environment and humanity, showing that harmony is the result of respecting the environment.[185] The film also references Miyazaki's mother; the child protagonists' mother is bedridden.[186] As with Laputa, Miyazaki wrote lyrics for Totoro's end theme.[187] Miyazaki struggled with the film's script until he read a Mainichi Graph story about Japan forty years prior, opting to set the film in the country before Tokyo's expansion and the advent of television. Miyazaki has subsequently donated money and artwork to fund preservation of the forested land in Saitama Prefecture, in which the film is set.[186]

Production of My Neighbor Totoro began in April 1987 and took exactly a year;[188] it was released on April 16, 1988.[189] While the film received critical acclaim, it was only moderately successful at the box office.[190][191] Studio Ghibli approved merchandising rights in 1990, which led to major commercial success; merchandise profits alone were able to sustain the studio for years.[190] The film was labeled a cult classic,[191] eventually gaining success in the United States after its release in 1993,[190] where its home video release sold almost 500,000 copies.[192] Akira Kurosawa said the film moved him, naming it among his hundred favorite films—one of few Japanese films to be named.[193] An asteroid discovered by Takao Kobayashi in December 1994 was named after the film: 10160 Totoro.[194]

In 1987, Studio Ghibli acquired the rights to create a film adaptation of Eiko Kadono's novel Kiki's Delivery Service. Miyazaki's work on My Neighbor Totoro prevented him from directing the adaptation; he acted as producer, while Sunao Katabuchi was chosen as director and Nobuyuki Isshiki as script writer.[195][196] Miyazaki's dissatisfaction of Isshiki's first draft led him to make changes to the project, ultimately taking the role of director. Kadono expressed her dissatisfaction with the differences between the book and screenplay, but Miyazaki and Takahata convinced her to let production continue.[197][196] The film was originally intended to be a 60-minute special, but expanded into a feature film after Miyazaki completed the storyboards and screenplay.[198] Miyazaki felt the struggles of the protagonist, Kiki, reflected the feelings of young girls in Japan yearning to live independently in cities,[199] while her talents reflected those of real girls, despite her magical powers.[200] In preparation for production, Miyazaki and other senior staff members traveled to Sweden, where they captured eighty rolls of film in Stockholm and Visby, the former being the primary inspiration behind the film's city.[201] Kiki's Delivery Service premiered on July 29, 1989;[202] it was critically successful, winning the Anime Grand Prix. With more than 2.6 million tickets sold,[203] it earned ¥2.15 billion at the box office[204] and was the highest-grossing film in Japan in 1989.[205] Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli personally approved the subsequent English translations.[197]

From March to May 1989, Miyazaki's manga Hikōtei Jidai was published in the magazine Model Graphix,[206] based on an earlier film idea he had assigned to a younger director in 1988 that fell through due to creative differences.[207][130] Miyazaki began production on a 45-minute in-flight film for Japan Airlines based on the manga; Suzuki extended it into a feature-length film, titled Porco Rosso, as expectations and budget grew.[207][208] Miyazaki began work on the film with little assistance, as its production overlapped with Takahata's Only Yesterday (1991), which Miyazaki co-produced.[209][210] The outbreak of the Yugoslav Wars in 1991 affected Miyazaki, prompting a more sombre tone for Porco Rosso;[211] the Croatian War of Independence moved the film's setting from Dubrovnik to the Adriatic Sea.[212] Miyazaki later referred to the film as "foolish", as its mature tones were unsuitable for children,[213] noting he had made it for his "own pleasure" due to his love of planes.[214]

Except for the Curtiss R3C-2, all planes in Porco Rosso are original creations from Miyazaki's imagination, based on his childhood memories.[215] The film also pays homage to the work of Fleischer Studios and Winsor McCay, which were influential to Japanese animation in the 1940s.[216] The film featured anti-war themes, which Miyazaki would later revisit.[217][218] The protagonist's name, Marco Pagot, is the same as an Italian animator with whom Miyazaki had worked on Sherlock Hound.[219] Some female staff at Studio Ghibli considered the film's Piccolo factory—led by a man and staffed by women—an intentional mirroring of Studio Ghibli's staff, of whom many are women; some viewed it as Miyazaki's respect for their work ethic, though others felt it implied women were easier to exploit.[220] Japan Airlines remained a major investor in the film, resulting in its initial premiere as an in-flight film,[211] prior to its theatrical release on July 18, 1992.[221] It was Miyazaki's first film not to top Animage's yearly reader poll, which has been attributed to its mature focus.[222] The film was commercially successful, becoming the highest-grossing film of the year in Japan;[149] it remained one of the highest-grossing films for several years.[223]

During production of Porco Rosso, Miyazaki spearheaded work on Studio Ghibli's new studio in Koganei, Tokyo, designing the blueprints, selecting materials, and working with builders.[149] The studio opened in August 1992,[224] and the staff moved in shortly after Porco Rosso's release.[149] Around this time, Miyazaki started work on the final volumes of the manga Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, which he created in-house at Studio Ghibli.[225] In November, two television spots directed by Miyazaki were broadcast by Nippon Television Network (NTV): Sora Iro no Tane, a 90-second spot adapted from the illustrated story Sora Iro no Tane by Rieko Nakagawa and Yuriko Omura; and Nandarou, a series of four five-second advertisements featuring an undefinable creature.[226][227] Miyazaki assisted with the concept of Takahata's Pom Poko (1994),[226] and designed the storyboards and wrote the screenplay for Kondō's Whisper of the Heart (1995), being particularly involved in the latter's fantasy sequences.[228] Critics and fans began to see Kondō as "the heir-apparent" to Studio Ghibli.[225]

Global emergence (1995–2001)

[edit]

Miyazaki's next film, Princess Mononoke, originated in sketches he had made in the late 1970s, based on Japanese folklore and the French fairytale Beauty and the Beast; his original ideas were rejected, and he published his sketches and initial story idea in a book in 1982.[230][231] He revisited the project after the success of Porco Rosso allowed him more creative freedom.[230] He chose the Muromachi period for the setting as he felt Japanese people stopped worshiping nature and began attempting to control it. Miyazaki began writing the film's treatment in August 1994. While experiencing writer's block in December,[232] Miyazaki accepted a request to create On Your Mark, a music video for the song by Chage and Aska. He experimented with computer animation to supplement traditional animation. On Your Mark premiered as a short before Whisper of the Heart.[233] The video's story was partly inspired by the Chernobyl disaster.[234] Miyazaki intentionally made it cryptic, wanting viewers to interpret it themselves.[235] Despite the video's popularity, Suzuki said it was not given "100 percent" focus.[236]

Miyazaki completed Princess Mononoke's formal proposal in April 1995 and began working on storyboards in May.[232] He had intended it to be his final directorial work at Studio Ghibli, citing his poorer eyesight and physical pains.[225][237][238] In July 1996, the Walt Disney Company offered Tokuma Shoten a deal to distribute Studio Ghibli's films worldwide (except for Southeast Asia) through its Buena Vista and Miramax Films brands. Miyazaki approved the deal, not personally interested in the money and wanting to support Tokuma Shoten, who had earlier supported him.[239] In May 1995, Miyazaki took four art directors to Yakushima—which had previously provided inspiration for Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind—to research the forests as inspiration; another art director, Kazuo Oga, traveled to Shirakami-Sanchi.[240] The landscapes in the film were inspired by Yakushima.[241] In Princess Mononoke, Miyazaki revisited the ecological and political themes of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind.[242] His historical research, including that of Eiichi Fujimori, led him to the conclusion that women had more freedom during the prehistoric Jomon period, and he opted to focus on ordinary people in society.[243]

Miyazaki felt the melancholy of the protagonist, Ashitaka, reflected his own attitude, while he compared Ashitaka's scar to modern physical conditions that children endure, like AIDS. Animation work began in July 1995,[244] before the storyboards were completed—a first for Miyazaki.[212] He supervised the 144,000 cels in the film, about 80,000 of which were key animation.[245][246] Princess Mononoke was produced with an estimated budget of ¥2.35 billion (approximately US$23.5 million),[247] making it the most expensive Japanese animated film at the time.[248] Approximately fifteen minutes of the film uses computer animation: about five minutes uses techniques such as 3D rendering, digital composition, and texture mapping; the remaining ten minutes uses digital ink and paint.[229] While the original intention was to digitally paint 5,000 of the film's frames, time constraints doubled this, though it remained below ten percent of the final film.[249] Animation was completed in mid-June 1997.[232] Miyazaki collaborated directly with Hisaishi on the soundtrack from early in production; Hisaishi wrote an "image album" of pieces inspired by the story, which were reworked as production continued.[238]

Upon its premiere on July 12, 1997,[250] Princess Mononoke was critically acclaimed, becoming the first animated film nominated for the Japan Academy Film Prize for Picture of the Year, which it won.[251] The film was also commercially successful; it was watched by twelve million people by November, grossing US$160 million,[252] and became the highest-grossing film in Japan for several months.[253][h] Its home video release sold over two million copies within three weeks,[i] and over four million by December 1998.[240] For the North American release, Miramax sought to make some cuts to obtain a lower rating than PG-13, but Studio Ghibli refused.[254] Neil Gaiman wrote the English-language script; he met Miyazaki in September 1999, when he traveled to the United States for the film's release and expressed his pleasure at Gaiman's work.[255][256] While it was largely unsuccessful at the American box office, grossing about US$2.3 million,[257] it was seen as the introduction of Studio Ghibli to global markets.[237]

In 1997, Miyazaki contributed to Visionaire, an arthouse magazine.[258] Tokuma Shoten merged with Studio Ghibli in June 1997.[224] Within walking distance of Studio Ghibli, Miyazaki designed his private office, which he named Buta-ya (meaning "pig house").[259][151] It was intended as his retirement office for personal projects;[260] he held his farewell party there in January 1998,[259] having left Studio Ghibli on January 14 to be succeeded by Kondō. However, Kondō's death on January 21 impacted Miyazaki, and within days it was announced he would return to Studio Ghibli to direct a new film.[212][259] A manga by Miyazaki, Doromamire no Tora, was published in Model Graphix in December 1998, based on a book by German tank commander Otto Carius.[261] Miyazaki officially returned to Studio Ghibli as its leader on January 16, 1999, taking an active role in employee organization.[260][212]

From 1998, Miyazaki worked on designs for the Ghibli Museum, dedicated to showcasing the studio's works, including several exclusive short films, for which production began in July 1999. Construction for the museum began in March 2000, and it officially opened on October 1, 2001, featuring the short film Kujiratori. Miyazaki served as its executive director.[262] In 1999, a Japanese theme park engaged Studio Ghibli to create a 20-minute short film about cats; Miyazaki agreed on the condition that it featured returning characters from Whisper of the Heart. Aoi Hiiragi wrote a manga based on the concept, titled Baron: The Cat Returns. When the theme park withdrew, Miyazaki expanded the idea into a 45-minute film and, wanting to foster new talent at the studio, assigned it to first-time director Hiroyuki Morita.[263][264] The film was released as The Cat Returns in 2002.[265]

Miyazaki's next film was conceived while on vacation at a mountain cabin with his family and five young girls who were family friends. Miyazaki realized he had not created a film for 10-year-old girls and set out to do so. He read shōjō manga magazines like Nakayoshi and Ribon for inspiration but felt they only offered subjects on "crushes and romance", which is not what the girls "held dear in their hearts"; he decided to produce the film about a female heroine whom they could look up to,[266] based on two of the girls he had met.[267] Production of the film, titled Spirited Away, commenced in 2000 on a budget of ¥1.9 billion (US$15 million). As with Princess Mononoke, the staff experimented with computer animation, but kept the technology at a level to enhance the story, not to "steal the show".[268] Spirited Away deals with symbols of human greed, symbolizing the 1980s Japanese asset price bubble,[269] and a liminal journey through the realm of spirits.[270][j] The film was released on July 20, 2001; it received critical acclaim, winning the Japan Academy Film Prize for Picture of the Year.[271] [272] The film was commercially successful, selling a record-breaking 21.4 million tickets and earning ¥30.4 billion (US$289.1 million) at the box office.[273][274] It became the highest-grossing film in Japan, a record it maintained for almost 20 years,[275][k] and was the first Japanese film to earn US$200 million internationally, prior to its American release.[273]

Kirk Wise directed the English-language version; Disney Animation's John Lasseter wanted Miyazaki to travel to the United States to work on the translated version, but Miyazaki trusted Lasseter to handle it.[276] Spirited Away's hopping lamp character is seen as an homage to Lasseter's character Luxo Jr.[277] The film's successful American release through Buena Vista cemented Studio Ghibli's reputation in Western regions[278][279][280] and established Miyazaki's popularity in North America;[281] it was the first animated film to win the Golden Bear at the Berlin International Film Festival (tied with Blood Sunday)[276] and the first Japanese film to win Best Animated Feature at the Academy Awards,[278] alongside several other accolades.[282] It has been frequently ranked among the greatest films of the 21st century.[283][284][285] Upon completing the film, like with Princess Mononoke, Miyazaki declared it his last.[286] He traveled to France in December 2001 and the United States in September 2002 to promote the film.[287] Following the death of Tokuma in September 2000, Miyazaki served as the head of his funeral committee.[255] Miyazaki wrote and directed more short films for the Ghibli Museum: Koro no Daisanpo, which screened from January 2002, and Mei and the Kittenbus, which screened from October.[288] One of the short films, Imaginary Flying Machines, was later screened as in-flight entertainment by Japan Airlines alongside Porco Rosso.[289]

Later films (2001–2011)

[edit]Studio Ghibli announced the production of Howl's Moving Castle in September 2001, based on the novel by Diana Wynne Jones,[290] which Miyazaki had read in 1999.[291] Toei Animation's Mamoru Hosoda was originally selected to direct the film, but disagreements between Hosoda and Studio Ghibli executives led to the project's abandonment in 2002.[292][293] After six months, Studio Ghibli resurrected the project. Miyazaki was inspired to direct the film, struck by the image of a castle moving around the countryside; the novel does not explain how the castle moved, which led to Miyazaki's designs.[3] Some computer animation was used to animate the castle's movements,[294] though Miyazaki dictated it consist of no more than 10 percent of the film.[293] Miyazaki traveled to Colmar and Riquewihr in Alsace, France, to study the architecture and the surroundings for the film's setting,[295] while additional inspiration came from the concepts of future technology in Albert Robida's work.[296] The war featured in the film was thematically influenced by the 2003 invasion and subsequent war in Iraq, the events of which enraged Miyazaki.[297]

Howl's Moving Castle was released on November 20, 2004, and received widespread critical acclaim. The film received the Golden Osella for Technical Excellence at the 61st Venice International Film Festival,[298] and was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature.[299] In Japan, the film sold more than 1.1 million tickets within two days[300] and grossed a record US$14.5 million in its first week.[3] It became Japan's third-highest-grossing film,[300] and remains among the top rankings with a worldwide gross of over ¥19.3 billion.[301] Miyazaki received the honorary Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement award at the 62nd Venice International Film Festival in 2005.[302] He visited the United States in June 2005 to promote the film.[303]

In March 2005, Studio Ghibli split from Tokuma Shoten,[304] and Miyazaki became corporate director.[303] After Howl's Moving Castle, Miyazaki created some short films for the Ghibli Museum, for which he returned solely to traditional animation techniques;[294] all three began screening in January 2006.[305] Studio Ghibli obtained the rights to produce an adaptation of Ursula K. Le Guin's Earthsea novels in 2003;[306] Miyazaki had contacted her in the 1980s expressing interest but she declined, unaware of his work. Upon watching My Neighbor Totoro several years later, she expressed approval to the concept and met with Suzuki in August 2005, who wanted Miyazaki's son Goro to direct the film, as Miyazaki had wished to retire. Disappointed that Miyazaki was not directing but under the impression he would supervise his son's work, Le Guin approved of the film's production.[307] Miyazaki later publicly opposed and criticized Goro's appointment as director.[308] The film's designs were partly inspired by Miyazaki's manga The Journey of Shuna.[309] Upon Miyazaki's viewing of the film, he wrote a message for his son: "It was made honestly, so it was good".[310]

In February 2006, Miyazaki traveled to the United Kingdom to research A Trip to Tynemouth (based on Robert Westall's "Blackham's Wimpy"), for which he designed the cover, created a short manga, and worked as editor;[311] it was released in October.[312] Miyazaki's next film, Ponyo, began production in May 2006.[313] It was initially inspired by "The Little Mermaid" by Hans Christian Andersen, though began to take its own form as production continued.[314] Miyazaki aimed for the film to celebrate the innocence and cheerfulness of a child's universe.[313] He was intimately involved with the artwork, preferring to draw the sea and waves himself, as he enjoyed experimenting.[315] Two short films—Looking for a Home and Water Spider Monmon—were made for the Ghibli Museum shortly before Ponyo entered production as animation experiments for sea life.[316]

Ponyo features 170,000 frames—a record for Miyazaki.[317] Its seaside village was inspired by Tomonoura, a town in Setonaikai National Park, where Miyazaki stayed in 2004.[318] The main character, Sōsuke, is based on Gorō.[319] Following its release on July 19, 2008, Ponyo was critically acclaimed, receiving Animation of the Year at the 32nd Japan Academy Film Prize.[320] The film was also a commercial success, earning ¥10 billion (US$93.2 million) in its first month[319] and ¥15.5 billion by the end of 2008, placing it among the highest-grossing films in Japan;[321] its box office earnings outpaced its ¥3.4 billion budget fivefold.[322] In April 2008, Miyazaki founded Home of the Three Bears, a preschool for the children of Studio Ghibli employees for which he had worked on early architectural plans.[323]

In early 2009, Miyazaki began writing a manga called Kaze Tachinu (風立ちぬ, The Wind Rises), telling the story of Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighter designer Jiro Horikoshi. The manga was first published in two issues of the Model Graphix magazine, published on February 25 and March 25, 2009.[324] For the Ghibli Museum, Miyazaki wrote the short film A Sumo Wrestler's Tail, directed by Akihiko Yamashita, and wrote and directed Mr. Dough and the Egg Princess; both started screening in 2010.[325] From July 2008, Miyazaki planned and produced the film Arrietty (2010),[326] for which he co-wrote the screenplay with Keiko Niwa,[327] based on the 1952 novel The Borrowers;[328] it was the directorial debut of Hiromasa Yonebayashi, who had started as an inbetween artist on Princess Mononoke.[329] Miyazaki and Niwa wrote the screenplay for From Up on Poppy Hill (2011), based the 1979–1980 manga Coquelicot-zaka kara; the film, directed by Goro Miyazaki, was the highest-grossing Japanese film in the country in 2011 and won Animation of the Year at the Japan Academy Awards.[330][331]

Retirement and return (2012–present)

[edit]Miyazaki wanted his next film to be a sequel to Ponyo, but Suzuki convinced him to instead adapt Kaze Tachinu to film.[332] In November 2012, Studio Ghibli announced the production of The Wind Rises, based on Kaze Tachinu, to be released as a double bill alongside Takahata's The Tale of the Princess Kaguya;[333] the latter was ultimately delayed.[334] Miyazaki was inspired to create The Wind Rises after reading a quote from Horikoshi: "All I wanted to do was to make something beautiful".[335] Several scenes in The Wind Rises were inspired by Tatsuo Hori's novel The Wind Has Risen (風立ちぬ), in which Hori wrote about his life experiences with his fiancée before she died from tuberculosis. The female lead character's name, Naoko Satomi, was borrowed from Hori's novel Naoko (菜穂子),[336] while the name of a German man, Hans Castorp, taken from Thomas Mann's The Magic Mountain.[337] Naoko's struggles with tuberculosis echo the illness of Miyazaki's mother, and Horikoshi's story of growing from a young boy dreaming of airplanes to an inspirational artist is reflective of Miyazaki's own life.[338]

The Wind Rises reflects Miyazaki's pacifist stance,[335] continuing the themes of his earlier works, despite stating that condemning war was not the intention of the film;[339] he felt that, despite his occupation, Horikoshi was not militant.[340] Miyazaki was moved by the film, the first of his own works to make him cry.[341] As Horikoshi, he cast Hideaki Anno, who had worked on Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind and later became known for creating Neon Genesis Evangelion.[342] The film premiered on July 20, 2013,[335] It received critical acclaim for its animation, narrative, and characters, though some viewers were critical of the film's focus on Horikoshi due to the impacts of his inventions and others were disappointed by its lack of fantastical elements.[343] It was named Animation of the Year at the 37th Japan Academy Film Prize[344] and was nominated for Best Animated Feature at the 86th Academy Awards.[345] It was commercially successful, grossing ¥11.6 billion (US$110 million) at the Japanese box office, becoming the highest-grossing film in Japan in 2013.[346] The film's production was documented in Mami Sunada's The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness.[342][347]

In September 2013, Miyazaki announced he was retiring from the production of feature films due to his age, but wished to continue working on the displays at the Ghibli Museum.[348][349] Miyazaki was awarded the Academy Honorary Award at the Governors Awards in November 2014.[350] He developed Boro the Caterpillar, an animated short film which was first discussed during pre-production for Princess Mononoke.[351] It was screened exclusively at the Ghibli Museum in July 2017.[352] Around this time, Miyazaki was working on a manga titled Teppo Samurai.[353] In February 2019, a four-part documentary was broadcast on the NHK network titled 10 Years with Hayao Miyazaki, documenting production of his films in his private studio.[354] In 2019, Miyazaki approved a musical adaptation of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, as it was performed by a kabuki troupe.[355]

In August 2016, Miyazaki proposed a new feature-length film, Kimi-tachi wa Dō Ikiru ka (titled The Boy and the Heron in English), on which he began animation work without receiving official approval.[352] The film opened in Japanese theaters on July 14, 2023.[356] It was preceded by a minimal marketing campaign, forgoing trailers, commercials, and advertisements, a response from Suzuki to his perceived oversaturation of marketing materials in mainstream films.[357] Despite claims that The Boy and the Heron would be Miyazaki's final film, Studio Ghibli vice president Junichi Nishioka said in September 2023 that Miyazaki continued to attend the office daily to plan his next film.[358] Suzuki said he could no longer convince Miyazaki to retire.[359] The Boy and the Heron won Miyazaki his second Academy Award for Best Animated Feature at the 96th Academy Awards,[360] becoming the oldest director to do so; Miyazaki did not attend the show due to his advanced age.[361]

Views

[edit]"If you don't spend time watching real people, you can't do this, because you've never seen it. Some people spend their lives interested only in themselves. Almost all Japanese animation is produced with hardly any basis taken from observing real people... It's produced by humans who can't stand looking at other humans. And that's why the industry is full of otaku !"

Hayao Miyazaki, January 2014[362]

Miyazaki has often criticized the state of the animation industry, stating that some animators lack a foundational understanding of their subjects and do not prioritize realism.[363] He is particularly critical of Japanese animation, saying that anime is "produced by humans who can't stand looking at other humans ... that's why the industry is full of otaku !".[362] He has frequently criticized otaku, including "fanatics" of guns and fighter aircraft, declaring it a "fetish" and refusing to identify himself as such.[364][365] He bemoaned the state of Disney animated films in 1988, saying "they show nothing but contempt for the audience".[366]

In 2013, Miyazaki criticized Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe's policies and the proposed Constitutional amendment that would allow Abe to revise the clause outlawing war as a means to settle international disputes.[l] Miyazaki felt Abe wished to "leave his name in history as a great man who revised the Constitution and its interpretation", describing it as "despicable"[368] and stating "People who don't think enough shouldn't meddle with the constitution".[369] In 2015, Miyazaki disapproved Abe's denial of Japan's military aggression, stating Japan "should clearly say that [they] inflicted enormous damage on China and express deep remorse over it".[368] He felt the government should give a "proper apology" to Korean comfort women who were forced to service the Japanese army during World War II and suggested the Senkaku Islands be "split in half" or controlled by both Japan and China.[217] After the release of The Wind Rises in 2013, some online critics labeled Miyazaki a "traitor" and "anti-Japanese", describing the film as overly "left-wing";[217] Miyazaki recognized leftist values in his movies, citing his influence by and appreciation of communism as defined by Karl Marx, but criticized the Soviet Union's political system.[370]

When Spirited Away was nominated at the 75th Academy Awards in 2003, Miyazaki refused to attend in protest of the United States's involvement in the Iraq War, and later said he "didn't want to visit a country that was bombing Iraq".[371] He did not publicly express this opinion at the request of his producer until 2009 when he lifted his boycott and attended San Diego Comic Con International as a favor to his friend John Lasseter.[371] Miyazaki also expressed his opinion about the terrorist attack at the offices of the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, criticizing the magazine's decision to publish the content cited as the catalyst for the incident; he felt caricatures should be made of politicians, not cultures.[372] In November 2016, Miyazaki believed "many of the people who voted for Brexit and Trump" were affected by the increase in unemployment due to companies "building cars in Mexico because of low wages and [selling] them in the US".[373] He did not think Donald Trump would be elected president, calling it "a terrible thing", but said Trump's political opponent Hillary Clinton was "terrible as well".[373]

Themes

[edit]Miyazaki's works are characterized by the recurrence of themes such as feminism,[374][375][376] environmentalism, pacifism,[377][378][379] love, and family.[380][381][382] His narratives are also notable for not pitting a hero against an unsympathetic antagonist;[383][384][385] Miyazaki felt Spirited Away's Chihiro "manages not because she has destroyed the 'evil', but because she has acquired the ability to survive".[386]

Miyazaki's films often emphasize environmentalism and the Earth's fragility.[387] Margaret Talbot stated Miyazaki dislikes modern technology, and believes much of modern culture is "thin and shallow and fake"; he anticipates a time with "no more high-rises".[388] Miyazaki felt frustrated growing up in the Shōwa period from 1955 to 1965 because "nature—the mountains and rivers—was being destroyed in the name of economic progress".[389] Peter Schellhase of The Imaginative Conservative identified that several antagonists of Miyazaki's films "attempt to dominate nature in pursuit of political domination, and are ultimately destructive to both nature and human civilization".[382] Miyazaki is critical of exploitation under both communism and capitalism, as well as globalization and its effects on modern life, believing "a company is common property of the people that work there".[390] Ram Prakash Dwivedi identified values of Mahatma Gandhi in the films of Miyazaki.[391]

Several of Miyazaki's films feature anti-war themes. Daisuke Akimoto of Animation Studies categorized Porco Rosso as "anti-war propaganda" and felt the protagonist, Porco, transforms into a pig partly due to his extreme distaste of militarism.[m] Akimoto also argues that The Wind Rises reflects Miyazaki's "antiwar pacifism", despite Miyazaki stating that the film does not attempt to "denounce" war.[392] Schellhase also identifies Princess Mononoke as a pacifist film due to the protagonist, Ashitaka; instead of joining the campaign of revenge against humankind, as his ethnic history would lead him to do, Ashitaka strives for peace.[382] David Loy and Linda Goodhew argue both Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind and Princess Mononoke do not depict traditional evil, but the Buddhist roots of evil: greed, ill will, and delusion; according to Buddhism, the roots of evil must transform into "generosity, loving-kindness and wisdom" in order to overcome suffering, and both Nausicaä and Ashitaka accomplish this.[393] When characters in Miyazaki's films are forced to engage in violence, it is shown as being a difficult task; in Howl's Moving Castle, Howl is forced to fight an inescapable battle in defense of those he loves, and it almost destroys him, though he is ultimately saved by Sophie's love and bravery.[382]

Suzuki described Miyazaki as a feminist in reference to his attitude to female workers.[394] Miyazaki has described his female characters as "brave, self-sufficient girls that don't think twice about fighting for what they believe in with all their heart", stating they may "need a friend, or a supporter, but never a saviour" and "any woman is just as capable of being a hero as any man".[395] Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind was lauded for its positive portrayal of women, particularly protagonist Nausicaä.[144][146] Schellhase noted the female characters in Miyazaki's films are not objectified or sexualized, and possess complex and individual characteristics absent from Hollywood productions.[382] Schellhase also identified a "coming of age" element for the heroines in Miyazaki's films, as they each discover "individual personality and strengths".[382] Gabrielle Bellot of The Atlantic wrote that, in his films, Miyazaki "shows a keen understanding of the complexities of what it might mean to be a woman". In particular, Bellot cites Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, praising the film's challenging of gender expectations, and the strong and independent nature of Nausicaä. Bellot also noted Princess Mononoke's San represents the "conflict between selfhood and expression".[396]

Miyazaki is concerned with the sense of wonder in young people, seeking to maintain themes of love and family in his films.[382] Michael Toscano of Curator found Miyazaki "fears Japanese children are dimmed by a culture of overconsumption, overprotection, utilitarian education, careerism, techno-industrialism, and a secularism that is swallowing Japan's native animism".[397] Schellhase wrote that several of Miyazaki's works feature themes of love and romance, but felt emphasis is placed on "the way lonely and vulnerable individuals are integrated into relationships of mutual reliance and responsibility, which generally benefit everyone around them".[382] He also found many of the protagonists in Miyazaki's films present an idealized image of families, whereas others are dysfunctional.[382]

Creation process and influences

[edit]Miyazaki forgoes traditional screenplays in his productions, instead developing the narrative as he designs the storyboards, stating "We never know where the story will go but we just keep working on the film as it develops".[398] Miyazaki has employed traditional animation methods in all of his films, drawing each frame by hand; computer-generated imagery has been employed in several of his later films, beginning with Princess Mononoke, to "enrich the visual look",[399] though he ensures each film can "retain the right ratio between working by hand and computer ... and still be able to call my films 2D".[400] He oversees every frame of his films.[401] For character designs, Miyazaki draws original drafts used by animation directors to create reference sheets, which are then corrected by Miyazaki in his style.[402]

Miyazaki has cited several Japanese artists as his influences, including Sanpei Shirato,[24] Osamu Tezuka, Soji Yamakawa,[26] and Isao Takahata,[403] and Western artists and animators like Frédéric Back,[398] Jean Giraud,[124] Paul Grimault,[398] Yuri Norstein,[404] and animation studio Aardman Animations (specifically the works of Nick Park).[405][n] A number of authors have also influenced his works, including Lewis Carroll,[400] Roald Dahl,[407] Ursula K. Le Guin,[131] Philippa Pearce, Rosemary Sutcliff, and Antoine de Saint-Exupéry,[34] Specific works that have influenced Miyazaki include Animal Farm (1945),[400] The Snow Queen (1957),[398] and The King and the Mockingbird (1980);[400] The Snow Queen is said to be the true catalyst for Miyazaki's filmography, influencing his training and work.[408] When animating young children, Miyazaki often takes inspiration from his friends' children and memories of his own childhood.[409]

Personal life

[edit]

Miyazaki's wife, Akemi Ōta (大田朱美), was born in 1938 and hired as an inbetween artist at Toei Animation in 1958, working on Panda and the Magic Serpent and Alakazam the Great (1960).[410] She and Miyazaki met at Toei in 1964,[410][3] and they married in October 1965.[37] At Toei, they worked together on The Great Adventure of Horus, Prince of the Sun and The Wonderful World of Puss 'n Boots.[410] They have two sons: Goro, born in January 1967, and Keisuke, born in April 1969.[54] Becoming a father changed Miyazaki and he tried to produce work to please his children.[53]

Miyazaki initially fulfilled a promise to his wife that they would both continue to work after Goro's birth, dropping him off at preschool for the day; however, upon seeing Goro's exhaustion walking home one day, Miyazaki decided they could not continue, and his wife quit in 1972 to stay at home and raise their children.[411][410] She was reluctant to do so but considered it necessary to allow Miyazaki to focus on his work.[410] Miyazaki's dedication to his work harmed his relationship with his children as he was often absent. Goro watched his father's works to "understand" him since the two rarely talked.[412] Miyazaki said he "tried to be a good father, but in the end [he] wasn't a very good parent".[411] During production of Tales from Earthsea in 2006, Goro said his father "gets zero marks as a father but full marks as a director of animated films".[412][o]

Goro worked at a landscape design firm before beginning to work at the Ghibli Museum;[3][411] he designed the garden on its rooftop and eventually became its curator.[3][53] Keisuke studied forestry at Shinshu University and works as a wood artist;[3][411][413] he designed a woodcut print that appears in Whisper of the Heart.[413] Miyazaki's niece, Mei Okuyama, who was the inspiration behind the character Mei in My Neighbor Totoro, is married to animation artist Daisuke Tsutsumi.[414]

Legacy

[edit]Miyazaki was described as the "godfather of animation in Japan" by BBC's Tessa Wong in 2016, citing his craftsmanship and humanity, the themes of his films, and his inspiration to younger artists.[415] Courtney Lanning of Arkansas Democrat-Gazette named him one of the world's greatest animators, comparing him to Osamu Tezuka and Walt Disney;[416] Miyazaki has been called "the Disney of Japan", though Helen McCarthy considered comparison to Akira Kurosawa more appropriate due to the combination of grandeur and sensitivity in his work, dubbing him "the Kurosawa of animation".[417] Swapnil Dhruv Bose of Far Out Magazine wrote that Miyazaki's work "has shaped not only the future of animation but also filmmaking in general", and that it helped "generation after generation of young viewers to observe the magic that exists in the mundane".[418] Richard James Havis of South China Morning Post called him a "genius ... who sets exacting standards for himself, his peers and studio staff".[419] Paste's Toussaint Egan described Miyazaki as "one of anime's great auteurs", whose "stories of such singular thematic vision and unmistakable aesthetic" captured viewers otherwise unfamiliar with anime.[420] Miyazaki became the subject of an exhibit at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures in Los Angeles in 2021, featuring over 400 objects from his films.[421]

Miyazaki has frequently been cited as an inspiration to numerous animators, directors and writers around the world, including Wes Anderson,[422] Tony Bancroft,[239] James Cameron,[423] Barry Cook,[239] Dean DeBlois,[424] Guillermo del Toro,[425] Pete Docter,[426] Mamoru Hosoda,[427] Bong Joon-ho,[428] Travis Knight,[429] John Lasseter,[430] Nick Park,[431] Henry Selick,[432] Makoto Shinkai,[433] and Steven Spielberg.[434] Glen Keane said Miyazaki is a "huge influence" on Walt Disney Animation Studios and has been "part of our heritage" ever since The Rescuers Down Under (1990).[435] The Disney Renaissance era was also prompted by competition with the development of Miyazaki's films.[436] Artists from Pixar and Aardman Studios signed a tribute stating, "You're our inspiration, Miyazaki-san!"[431] He has also been cited as inspiration for video game designers including Shigeru Miyamoto on The Legend of Zelda[437] and Hironobu Sakaguchi on Final Fantasy,[438] as well as the television series Avatar: The Last Airbender,[439] and the video game Ori and the Blind Forest (2015).[440]

Several books have been written about Miyazaki by scholars such as Raz Greenberg, Helen McCarthy, and Susan J. Napier;[441] according to Jeff Lenburg, more papers have been written about Miyazaki than any other Japanese artist.[442] Studio Ghibli has searched for some time for Miyazaki and Suzuki's successor to lead the studio;[443] Kondō, the director of Whisper of the Heart, was initially considered, but died from a sudden heart attack in 1998.[444] Some candidates were considered by 2023—including Miyazaki's son Goro, who declined—but the studio was not able to find a successor.[445]

Selected filmography

[edit]- The Castle of Cagliostro (1979)

- Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984)

- Laputa: Castle in the Sky (1986)

- My Neighbor Totoro (1988)

- Kiki's Delivery Service (1989)

- Porco Rosso (1992)

- Princess Mononoke (1997)

- Spirited Away (2001)

- Howl's Moving Castle (2004)

- Ponyo (2008)

- The Wind Rises (2013)

- The Boy and the Heron (2023)

Awards and nominations

[edit]Miyazaki won the Ōfuji Noburō Award at the Mainichi Film Awards for The Castle of Cagliostro (1979), Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984), Laputa: Castle in the Sky (1986),[446] and My Neighbor Totoro (1988), and the Mainichi Film Award for Best Animation Film for Kiki's Delivery Service (1989),[447] Porco Rosso (1992),[448] Princess Mononoke (1997), Spirited Away (2001),[447] and Whale Hunt (2001).[448] Spirited Away and The Boy and the Heron were awarded the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature,[271][360] while Howl's Moving Castle (2004) and The Wind Rises (2013) received nominations.[299][345] He was named a Person of Cultural Merit by the Japanese government in November 2012, for outstanding cultural contributions.[449] Time named him one of the 100 most influential people in the world in 2005 and 2024,[303][450] and Gold House honored him on its Most Impactful Asians A100 list in 2024.[451] He was an honoree of the Ramon Magsaysay Award in 2024 for his usage of art to "illuminate the human condition".[452] Miyazaki's other accolades include several Annie Awards,[453][454][455] Japan Academy Film Prizes,[456][457][344] Kinema Junpo Awards,[458][459] and Tokyo Anime Awards.[332][460][461]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Miyazaki's brothers are Arata (born July 1939), Yutaka (born January 1944), and Shirou (born 1945).[1][4] Influenced by their father, Miyazaki's brothers went into business; Miyazaki's son Goro believes this gave him a "strong motivation to succeed at animation".[3]

- ^ Miyazaki admitted later in life that he felt guilty over his family's profiting from the war and their subsequent affluent lifestyle.[7]

- ^ a b Miyazaki based the character Captain Dola from Laputa: Castle in the Sky on his mother, noting "My mom had four boys, but none of us dared oppose her".[17] Other characters inspired by Miyazaki's mother include: Yasuko from My Neighbor Totoro, who watches over her children while suffering from illness; Sophie from Howl's Moving Castle, who is a strong-minded and kind woman;[18] and Toki from Ponyo.[11][19]

- ^ During his three-month training period at Toei Doga, Miyazaki's salary was ¥18,000.[37]

- ^ Miyazaki and Giraud became friends,[124] and Monnaie de Paris held an exhibition of their work titled Miyazaki et Moebius: Deux Artistes Dont Les Dessins Prennent Vie (Two Artists's Drawings Taking on a Life of Their Own) from December 2004 to April 2005; both artists attended the opening of the exhibition.[125]

- ^ Takahata refused to sign the paperwork to found the company, feeling that an artist should not be involved in such business documents. Regardless, he and Miyazaki are considered the studio's founders.[153][154]

- ^ According to Suzuki, Studio Ghibli was the successor of the Tokuma Shoten subsidiary company Iraka Planning—creators of Tempyō no Iraka (1980)—from which it inherited ¥36 million in outstanding debts.[156]

- ^ Princess Mononoke was eclipsed as the highest-grossing film in Japan by Titanic, released several months later.[253]

- ^ According to Screen Digest, about 20% of Princess Mononoke's two million copies sold were to first-time buyers of home videos.[240]

- ^ Protagonist Chihiro stands outside societal boundaries in the supernatural setting. The use of the word kamikakushi (literally "hidden by gods") within the Japanese title reinforces this symbol. Reider (2005) states: "Kamikakushi is a verdict of 'social death' in this world, and coming back to this world from Kamikakushi meant 'social resurrection'."[270]

- ^ Spirited Away was eclipsed as the highest-grossing film in Japan by Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba the Movie: Mugen Train in December 2020.[275]

- ^ Abe's party proposed the amendment to Article 96 of the Constitution of Japan, a clause that stipulates procedures needed for revisions. Ultimately, this would allow Abe to revise Article 9 of the Constitution, which outlaws war as a means to settle international disputes.[367]

- ^ Akimoto (2014) states: "Porco became a pig because he hates the following three factors: man (egoism), the state (nationalism) and war (militarism)."[218]

- ^ An exhibit based upon Aardman Animations's works ran at the Ghibli Museum from 2006 to 2007.[405] Aardman Animations founders Peter Lord and David Sproxton visited the exhibition in May 2006, where they met Miyazaki.[406]

- ^ Original text: "私にとって、宮崎駿は、父としては0点でも、アニメーション映画監督としては満点なのです。"

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Lenburg 2012, p. 11.

- ^ Miyazaki 1996, p. 435.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Talbot 2005.

- ^ a b c d e McCarthy 1999, p. 26.

- ^ a b Lenburg 2012, pp. 11–12.

- ^ a b c Miyazaki 1988.

- ^ Lenburg 2012, p. 12.

- ^ Miyazaki 1996, p. 208.

- ^ a b c Miyazaki 1996, p. 209.

- ^ Lenburg 2012, p. 60.

- ^ a b c Han 2020.

- ^ Schley 2023.

- ^ Miyazaki 1996, p. 239.

- ^ Arakawa 2019, 14:00.

- ^ a b Berton 2020, p. 11.

- ^ Lenburg 2012, p. 14.

- ^ Bayle 2017.

- ^ Arakawa 2019, 23:28.

- ^ Arakawa 2019, 29:51.

- ^ Lenburg 2012, p. 40.

- ^ Arakawa 2019, 21:82.

- ^ a b c Miyazaki 2009, p. 431.

- ^ Lenburg 2012, pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b c McCarthy 1999, p. 27.

- ^ Miyazaki 1996, p. 193.

- ^ a b c McCarthy 1999, p. 28.

- ^ Comic Box 1982, p. 80.

- ^ a b c d e f Miyazaki 1996, p. 436.

- ^ a b Lenburg 2012, p. 15.

- ^ McCarthy 1999, p. 29.

- ^ a b Miyazaki 2009, p. 70.

- ^ a b c Lenburg 2012, p. 16.

- ^ Miyazaki 1996, p. 200.

- ^ a b c d e McCarthy 1999, p. 30.

- ^ Batkin 2017, p. 141.

- ^ a b Mahmood 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Miyazaki 1996, p. 437.

- ^ McCarthy 1999, p. 217.

- ^ Lenburg 2012, pp. 18–19.

- ^ a b Lenburg 2012, p. 17.

- ^ Lenburg 2012, p. 18.

- ^ McCarthy 1999, pp. 217–218.

- ^ Odell & Le Blanc 2009, p. 37.

- ^ McCarthy 1999, p. 218.

- ^ a b Lenburg 2012, p. 19.

- ^ McCarthy 1999, p. 31.

- ^ a b LaMarre 2009, pp. 56ff.

- ^ a b Greenberg 2018, p. 17.

- ^ McCarthy 1999, p. 38.

- ^ Anime News Network 2001.

- ^ Drazen 2002, pp. 254ff.

- ^ Berton 2020, p. 14.

- ^ a b c Lenburg 2012, p. 20.

- ^ a b c d Miyazaki 1996, p. 438.

- ^ a b McCarthy 1999, p. 219.

- ^ a b c Comic Box 1982, p. 111.

- ^ a b c Animage 1983.

- ^ Lenburg 2012, p. 22.

- ^ Greenberg 2018, p. 31.

- ^ a b Odell & Le Blanc 2009, p. 39.

- ^ a b McCarthy 1999, p. 220.

- ^ Miyazaki 1996, p. 194.

- ^ a b McCarthy 1999, p. 27, 219.

- ^ Greenberg 2018, p. 26.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i McCarthy 1999, p. 39.

- ^ Lenburg 2012, p. 24.

- ^ a b Lenburg 2012, p. 28.

- ^ a b Lenburg 2012, p. 26.

- ^ Greenberg 2018, p. 54.

- ^ a b Takahata, Miyazaki & Kotabe 2014.

- ^ Greenberg 2018, pp. 32–33.

- ^ a b Greenberg 2018, p. 33.

- ^ Berton 2020, p. 91.

- ^ McCarthy 1999, p. 221.

- ^ Odell & Le Blanc 2009, p. 47.

- ^ McCarthy 1999, pp. 221–222.

- ^ Greenberg 2018, p. 36.

- ^ a b c Miyazaki 1996, p. 440.

- ^ Greenberg 2018, p. 38.

- ^ Lenburg 2012, p. 29.

- ^ Lenburg 2012, pp. 29–30.

- ^ a b Berton 2020, p. 98.

- ^ a b McCarthy 1999, p. 223.

- ^ a b Miyazaki 1996, p. 441.

- ^ Odell & Le Blanc 2009, p. 15.

- ^ Odell & Le Blanc 2009, p. 41.

- ^ Greenberg 2018, p. 81.

- ^ a b McCarthy 1999, p. 40.

- ^ Odell & Le Blanc 2009, p. 40.

- ^ a b Lenburg 2012, p. 33.

- ^ McCarthy 1999, p. 50.

- ^ Odell & Le Blanc 2009, p. 489.

- ^ a b c McCarthy 1999, p. 53.

- ^ a b Greenberg 2018, p. 65.

- ^ Greenberg 2018, p. 62.

- ^ McCarthy 1999, p. 56.

- ^ Macdonald 2005b.

- ^ Greenberg 2018, pp. 66–68.

- ^ Lenburg 2012, p. 34.

- ^ Lenburg 2012, p. 36.

- ^ a b c McCarthy 1999, p. 225.

- ^ Odell & Le Blanc 2009, p. 42.

- ^ a b c Lenburg 2012, p. 37.

- ^ Greenberg 2018, p. 74.

- ^ a b c d McCarthy 1999, p. 41.

- ^ Greenberg 2018, p. 107.

- ^ Greenberg 2018, p. 108.

- ^ Miyazaki 1996, p. 249.

- ^ Kanō 2006, pp. 37ff, 323.

- ^ Miyazaki 1996, p. 146.

- ^ Miyazaki 2007, p. 146.

- ^ Greenberg 2018, p. 88.

- ^ McCarthy 1999, pp. 73–74.

- ^ a b Saitani 1995, p. 9.

- ^ McCarthy 1999, p. 72.

- ^ a b Ryan.

- ^ a b c Lenburg 2012, p. 43.

- ^ Lenburg 2012, p. 39.

- ^ Miyazaki 1996, p. 94.

- ^ Miyazaki 2007, p. 94.

- ^ McCarthy 1999, p. 74.

- ^ Greenberg 2018, pp. 83–85.

- ^ Greenberg 2018, p. 95.

- ^ a b Cotillon 2005.

- ^ Montmayeur 2005.